The Great Resignation has been building for a generation. Here’s what happens next.

Five insights from Anne Helen Petersen and Charlie Warzel on how to build the flexible, inclusive, and connected workforce of the future

Posted March 30, 2022 by Eliza Sarasohn

The pandemic certainly created plenty of novel problems, but the biggest challenges businesses are facing today — from labor shortages to attracting and retaining a diverse, motivated workforce — have been building for decades.

That’s the argument that journalists Anne Helen Petersen and Charlie Warzel make in their book, Out of Office: the Big Problem and Bigger Promise of Working From Home. Inspired by the writers’ own rocky experiences with flexible work and informed by conversations with hundreds of workers across industries and sectors, the book is a wide-ranging discussion of the forces shaping the Great Resignation.

Petersen and Warzel are particularly well equipped to make sense of the challenges companies are facing as the pandemic enters its third year. Petersen’s 2020 book Can’t Event: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation explores the costs of labor trends like the gig economy. (The book grew out of her influential 2019 Buzzfeed article on the same topic.) Warzel is a contributing writer for the Atlantic magazine, where he writes about technology, media, and politics.

The authors recently joined executives from Future Forum working groups to discuss what they’ve learned through reporting on the pandemic’s effects on labor, and the steps business leaders can take today to build the flexible, inclusive, and connected workforce of the future. Here are five key insights from that conversation.

“We are at an inflection point for the way we work globally”

Warzel and Petersen’s focus on America’s remote workforce was animated in part by their own misadventures in working from home. In 2017 when they were both on staff at BuzzFeed News, the couple pulled up stakes in New York City and moved to Montana.

“We thought it was going to be this seamless, easy remote experience, but for me it was an absolute disaster,” Warzel admits. Keen to prove that he was worthy of the trust he’d asked his bosses to extend by leaving the office behind, he says he worked “ceaselessly” for months on end, obliterating the work/life boundaries that the traditional office had previously helped him maintain. “I was truly kind of ruining my life,” he says.

Through a series of searching conversations, Petersen and Warzel gradually wrestled remote work into a sustainable pattern. Then the pandemic hit, forcing workers the world over to “speed-run what we’d just been through,” Warzel says. They began to research the ways that the abrupt, global transition to working from home was affecting workers of all kinds.

As they dove into reporting, the authors increasingly recognized the ways that the pandemic stress-tested our systems, exposing generations-deep cracks in our institutions and highlighting self-defeating assumptions about workers’ productivity and motivations. The child-care crisis was squeezing working parents financially and hobbling companies’ efforts to diversify their workforces long before schools transitioned to online learning. A tech-saturated, always-on work culture was well on its way to fracturing our ability to focus and prioritize, while a longstanding tendency to reward employees for presenteeism instead of results had been gobbling up ever more of our free time and pushing employees toward burnout.

Now, as companies lay out strategies for returning to the office, Petersen says we’re “at an inflection point for the way we work globally.” Executives have a profound opportunity to help fix these deep-seated inequities, while attracting and retaining a happier, more diverse, and more productive workforce.

If our productivity comes in peaks, why does our workday look like a flat line?

While researching Out of Office, Petersen and Warzel gathered responses to detailed, open-ended surveys about work habits and attitudes from over 700 people. “At some point in their responses, even though we didn’t ask this question, people confessed that they basically get most of their work for the whole week done on like a three-hour sprint on a Thursday night after the kids go to bed,” Warzel says.

But the dominant model for generations of knowledge workers — on a schedule set by someone else, in an office environment they don’t control — has flattened our idea of workers into what Warzel calls “productivity nodes.” Our workdays are “not tailored to how people are doing their jobs, what their jobs really are, and what’s required to do them,” he says.

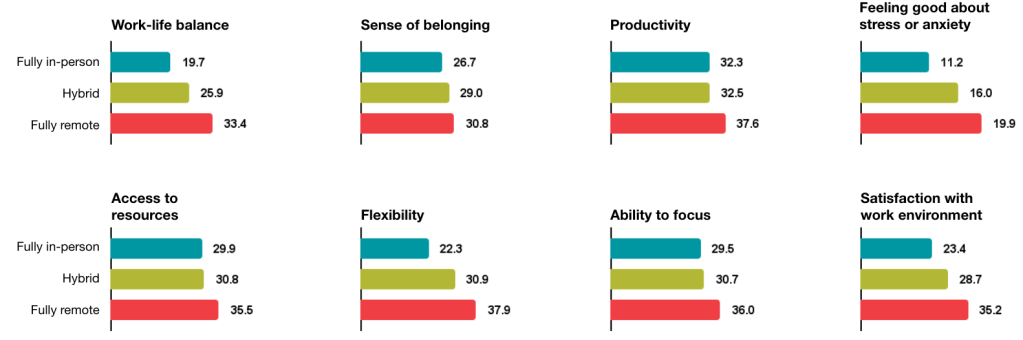

For many workers, one of the pandemic’s sunnier byproducts has been the greater freedom to let their individual wiring dictate when, where, and how they do their jobs. This sense of relief shows up in our latest Pulse survey: across all measures of employee engagement, from belonging to work-life balance to ability to manage stress and more, people with flexible work arrangements scored higher than people who are expected to show up to an office five days a week.

Hybrid and remote employees score higher than in-office workers on all experience measures

“It sounds simple, but really understanding how much work people actually need to do is crucial in making companies more efficient, but also making workers’ lives better,” Warzel says.

The social safety net is frayed. Schedule flexibility helps working families hang on.

Our Pulse survey consistently shows that flexibility — having some say in when and where you get your work done — is now a core work benefit, second only to compensation among the factors that knowledge workers consider when seeking new roles.

And it’s especially important for groups who’ve historically been underrepresented in knowledge work: mothers prioritize flexibility more than fathers, and in the U.S., Black, Hispanic and Latinx, and Asian American knowledge workers say they want flexibility more than their white colleagues. What’s more, survey respondents in the United States reported a greater need for flexibility than their counterparts in Australia, France, Germany, or Japan.

Petersen suspects these trends reflect the burdens on working families stuck in the midst of the nation’s worsening care crisis. The average American family spends 13% of its income on child care — nearly double the amount that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services considers affordable. And that’s if they can find care to begin with: 126,000 child-care professionals left the field during the pandemic. (French families, meanwhile, receive tax credits that cover 85% of the cost of day care until their kids are eligible to enter free public preschool at age 2 or 3.) “If we want to have mothers in the workforce, we have to figure out solutions to this care crisis,” Petersen asserts.

Petersen notes that this problem is much bigger than any one organization can resolve on its own, but flexible work policies can ease the burden on your employees. Absent widespread access to affordable child and elder care, giving employees the freedom to choose when and where they can get their work done is often the only thing that makes this precarious balance possible.

“If we fast forward five years and look at the difference in talent at organizations that have prepared for flexible work, who’ve continued to iterate and allow for this flexibility, and companies that are stuck in this one model, we’re going to see a huge discrepancy” in gender parity, Petersen predicts. Simply put, “If you don’t have that flexibility, your working mothers are going to leave.”

Use tools like team-level agreements to set crystal clear expectations for communication

Flexibility clearly shows huge potential to help your company attract and retain great people. But a hybrid workplace is not without pitfalls. As an executive, for instance, it might work best for your schedule to knock out a few emails before turning in for the night. But senior employees need to be “very mindful of when you respond to communications, and the ripple effect those communications have when they land in someone’s inbox, and how that works in terms of level of power in an organization,” Petersen warns.

In her own experience, responding to emails after hours might have been officially “frowned upon,” but in reality, “it was actually viewed consciously and unconsciously as a person doing their job well and being really committed.” If left unspoken and unchallenged, these norms can take a big bite out of your employees’ work-life balance.

Likewise, as hybrid working takes hold, a growing number of executives are also recognizing the potential for inequities to develop between employees who work in the office and those who want or need to work remotely. Our recent Pulse survey shows that a growing number of executives cite this “proximity bias” as their number one concern for implementing hybrid.

To make hybrid and remote work work, say Petersen and Warzel, executives must design new systems with intention, and commit to crystal clear communications about these new policies and expectations. That means modeling work-life balance — “Take your PTO, and when you take it, actually take time off” — Petersen says.

It also means you need to train managers to recognize when junior employees are pulling a lot of long hours — and intervene to discourage it. “It sounds counterintuitive, like you’re saying, ‘Do less work,’” Petersen says. “Really, you’re saying, ‘Cultivate good work hygiene that allows you to be present, not burn out, and not leave company.’ It’s actually a retention strategy.”

To combat proximity bias, use tools like team-level agreements to set and maintain clear expectations around how your employees should communicate throughout the workweek. The key, says Warzel, is “baking-in very real rules of how communication tools are supposed to be used.”

This is the moment when companies have so much to gain — or lose

Steering your company through a flexible work transformation is no easy task, Petersen and Warzel acknowledge, but it’s worth it. “Right now, you have people resigning en masse, totally burned out, with the highest levels of distrust against executives and corporations and employees thinking their bosses don’t have their best interests at heart,” says Petersen.

Requests for more flexibility are not “empty threats” — Future Forum research shows that 72% of workers who are dissatisfied with their current level of flexibility at work say that they are likely to look for a new job in the coming year, compared with 58% of total respondents.

It’s the companies that are ready and willing to invest in truly solving these entrenched, generational challenges now that will win the competition for talent and come out ahead in the long run — and turn the Great Resignation into a Great Rethink, Reset, and Renewal.